. It is a worrying situation because of the implications it has in terms of vegetation available to burn, fire behavior, and water resources from a firefighting point of view. The problem lies in the fact that parts of Europe have been suffering from this lack of significant precipitation for more than a year, further intensifying the effects. Many firefighting services have not even noticed the end of the last fire season, with a continuous occurrence of fires throughout the winter.

Looking at the meteorological and statistical data on forest fires, in general terms, what can you say about it?

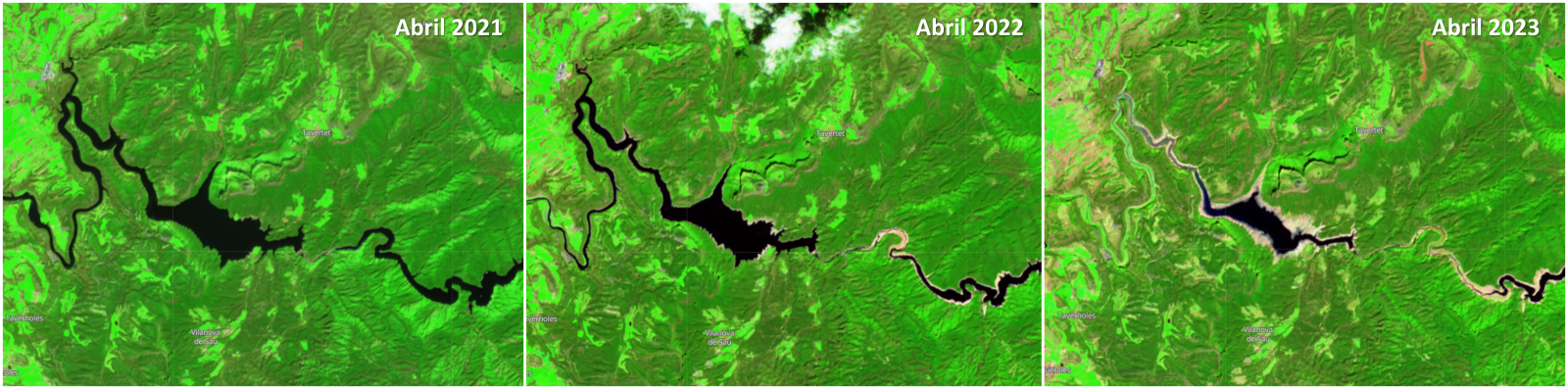

For southern Europe, we have been seeing very dry conditions not only this year but also for previous few years and the rainfall has not yet been able to overcome this situation... so we go through a multiyear drought. Also, I’ve been monitoring the water reservoirs in the Pyrenees, and they were extremely low in comparison to last year’s April, which was a fire year too, but also compared to 2021. Over the years, a significant and progressive drought has been developing, so conditions are not over, and we need a lot of rain and snow, of course, in the wintertime, to overcome these conditions.

Sentinel 2 images for the same site but from three successive years, comparing water levels in the Ter river and Sau reservoir, in Catalonia.

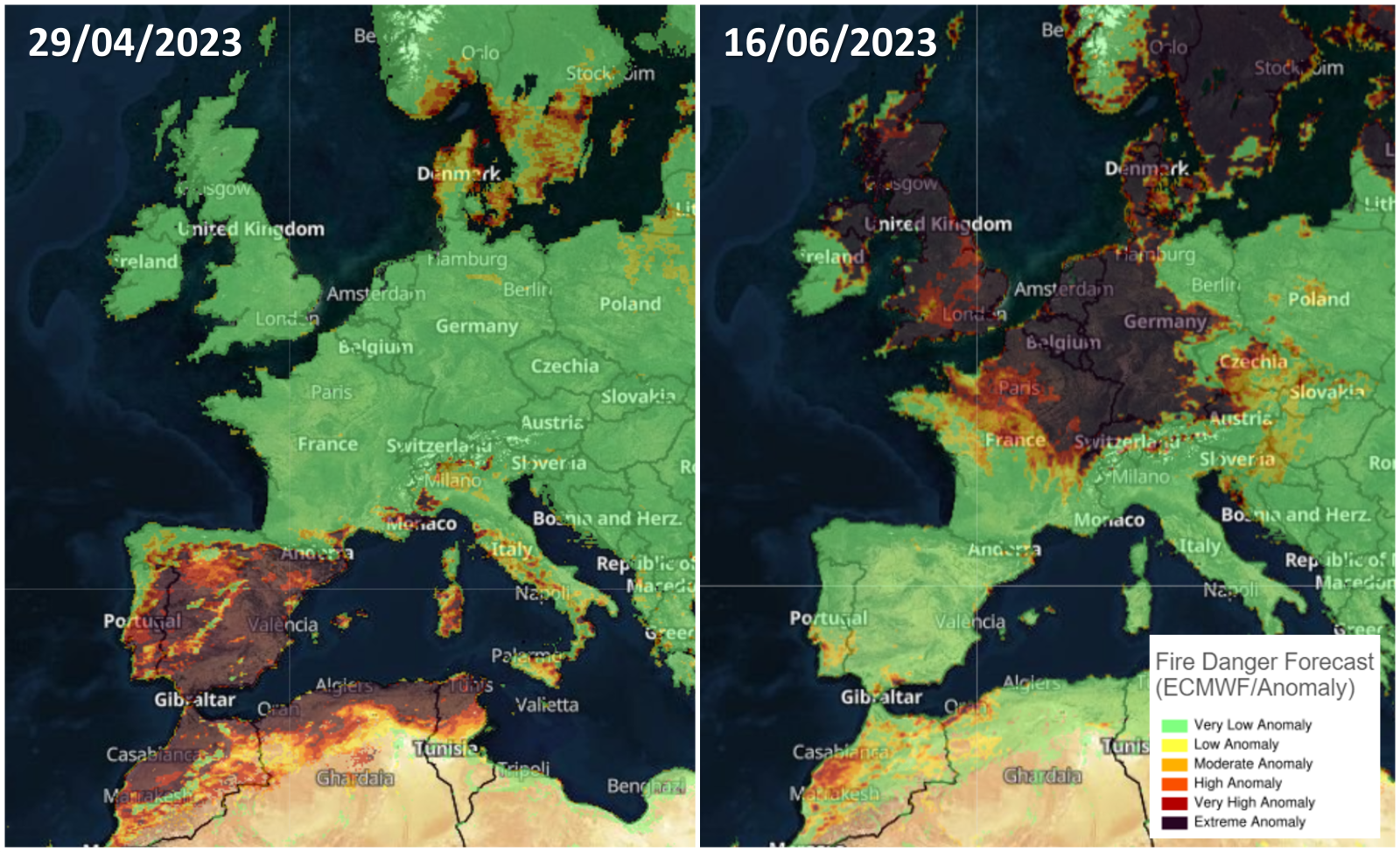

Currently, however, the conditions have completely shifted. Northern-Europe is mostly in a drought, whereas Southern-Europe has had large-scale precipitation events with even floodings as a result. Although the drought in Northern-Europe is causing (large) wildfires, now, the rain is at least some sort of a relief for e.g. Spain.

One problem here is that precipitation may not always be effective...

Any precipitation will always help but the thing is in what way the precipitation is falling… It differs greatly if it is more with the passage of a frontal zone, with the precipitation going on for many hours with a low to moderate intensity, which is better for the forest. For example, because that rain can enter the soil quite nicely as the intensity does not exceed the infiltration capacity of a (dry) soil, but when you have a lot of rain in the form of heavy thunderstorms, but over a relatively short period of time, most of the water is transported over the surface into rivers, so the water is not of use for the vegetation. The thing to realize is that is not just about evaporation and total amount of precipitation, if it’s very intense rain, especially if it’s over dry soil that it’s damaged it won’t allow the water to infiltrate. Therefore, you are not using the water effectively, and because of this you´ll need more water to overcome the situation.

The drought conditions, can we say that they are generalized for all of Europe?

The dry conditions are mainly affecting the southern Europe, like Spain, not comparable to the northern Europe. On the other hand, the Netherlands last year was extremely dry, but then when we went into wintertime and during the start of our Spring as well, it was extremely wet, overcoming these drought conditions. Groundwater levels have restored nicely. In the north of Italy, it’s interesting because they went from extreme drought to extreme precipitation, with floods we have seen in the news. There are differences within Europe. A single generalized condition for the whole of Europe is not what is expected, because the Jetstream, i.e., a narrow band of strong wind in the upper levels of the atmosphere causes differences within Europe. If you’re a bit North of it, the weather is generally unstable, whereas the areas south of it are stable. Generally speaking, if northern Europe is dry, southern Europe will be more wet, and the other way round, which is what we are experiencing.

Comparison of the two contrasting situations that usually occur in Europe. From the anomaly in the FWI hazard index, the drastic change in meteorological conditions for each region is intuited, leading to a very high and even extreme degree of danger for those sites. Source: FWI anomaly, GWIS.

From the point of view of wildfires, with the situation we have seen up to date, we cannot expect more than water-stressed forests and fuels of all sizes available to burn...

For the Iberian Peninsula in general, that can also count the south of France, with dry conditions going on for years, affecting the vegetation, becoming more stressed, turning the trees more brownish when they should be green, is something to consider when thinking about the new fire season. A clear sign that the vegetation is stressed and having difficulties, and that you will need moist conditions to revers it. Right now, as we speak, a wet period of rains is affecting the Peninsula, so it can get some relief. However, in the end, it’s important to wait and when this period of rains ends and when the dry conditions return. When you cross that line and start the fire season, you have to re-evaluate the vegetation, whether the rain has had a significant effect and where it is still not enough. Now, the fine fuel should give us a break, and the fires won’t be able to spread that fast… instead of speaking of a ROS (rate of spread) in km/h, we return to the m/h. But also, we cannot forget that anything that grows now, later, in terms of biomass, could become fuel. Here, in the Netherlands, we have had a wet winter and lot of grasses and fuels grew very rapidly. Two weeks ago, they were still green, moist, but now they have turned very yellow and have become fuels available to burn, so it’s important to keep this also in mind when talking about fuel management.

Let's go back to the meteorological processes that are currently taking place and that, in a certain way, are influencing what we are experiencing... lately, we have been hearing again about the phenomenon of “El Niño” / “La Niña”. Can we directly relate them to this situation of drought or even worsening conditions?

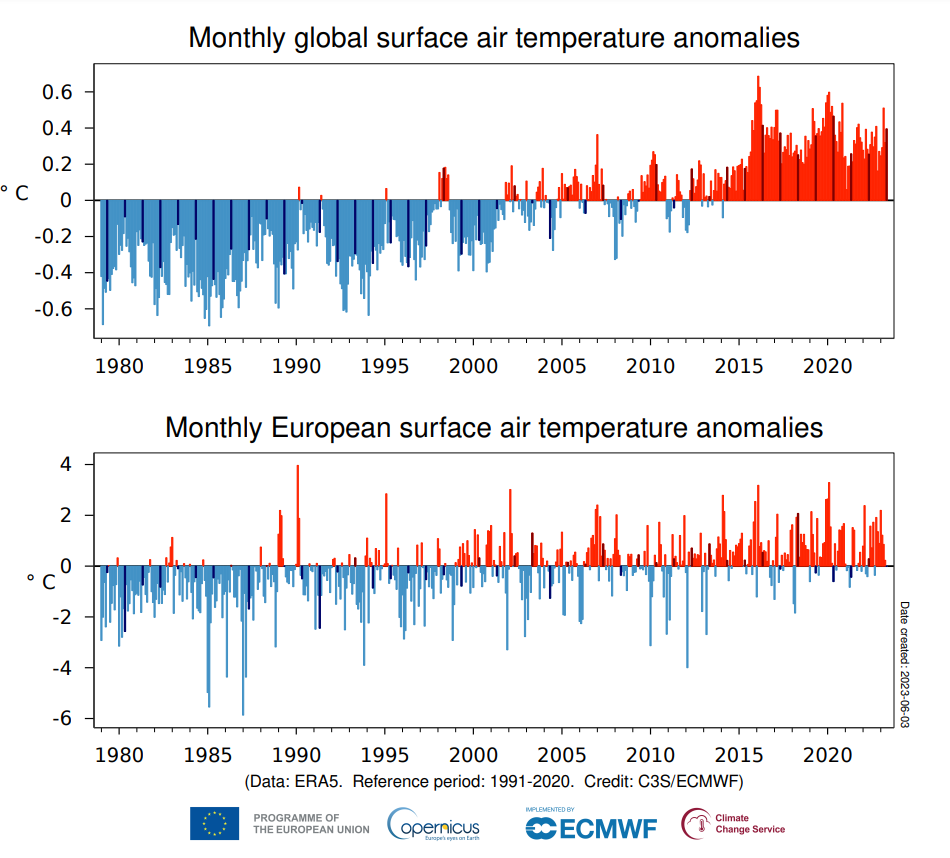

El Niño is a process most strongly experienced in Australia/Indonesia towards Chile, and southern America, where the whole process is happening, but in general, the effects can be experienced worldwide. In a very average way of talking, what you can expect is an above average temperature worldwide. So, when El Niño is happening, you would expect a temperature relatively high. Meteorologists have seen we are going towards El Niño situation and that could be quite strong. If we combine the warming effect of El Niño with the general global climate change, worldwide temperature could go really high. Like I said, southern America will have the strongest effect. In Europe is way less, and within Europe, the south experiences a stronger effect than the north. But in general, this increase in temperature could mean that it will affect the fires as well… El Niño, generally speaking, could result in more (intense) wildfires.

This phenomena is related to the sea water temperature in the ocean, in El Niño case, you will find relatively warm water near the coast of south America, meaning that you have a low pressure system installed, with a lot of precipitation, and on the other hand, near Australia, Indonesia, the water is relatively cold meaning it turn into a more stable conditions, with high pressure weather and dryer conditions than the usual weather type. La Niña is exactly the opposite. It shifts the warm water in South America into cold water, and the contrary in Australia, and therefore is related to colder temperatures.

The occurrence of this phenomenon is one of the processes contributing to the weather. It doesn’t have a direct meaning of a specific amount of extra heat waves in a certain area within a year. It’s something that you have to look in an average way as the same as the climate change, for example. When you are looking at a region, the effect of randomness of luck could mean that even El Niño conditions turn better where you wouldn’t expect it, but you have to keep in mind that average conditions are going towards a warmer global temperature.

Monthly average anomalies on a global and European scale. In the latter, although in the north, the temperature was 2.1°C cooler, elsewhere the warmest May on record for the period under consideration was observed. (Source: Surface air temperature for May 2023, Copernicus).

During this continuous drought episode, several times rains were forecasted and even though the radar was showing humidity at altitude, it was not precipitating… we understand that this was due to the high temperatures, right?

Let’s take Spain, where it seems that conditions over the years, are turning dryer and also within the soil. When you have sunshine radiating in and providing the energy for the soil, you have some processes going on… exchanging heat, energy within the atmosphere and warming the air; using some of the energy to evaporate moisture and some of the energy to warm up the soil.

In this process, for evaporation you need moisture, so when you are turning to a very dry condition, for a very long time, less of that energy goes into your evaporation because you don’t have the moisture for it, and hence more energy will go into the heating of the air, and also as a result, the drying out the air because the warmer the air gets, the lower the relative humidity goes. But when you have warmer conditions because of it, it enhances your evaporation, so the moisture that you still have, gets lost even more and the heating also activates more, so you go into a feedback loop that turns the conditions warmer and dryer, and so on.

To have this relatively dry conditions and specially in the lower levels of your atmosphere, depends on where your air comes from, not just the soil conditions. Now, if we higher up in the atmosphere and we find moisture, instability, and a shower or maybe a thunderstorm, the rain that is falling gets into the dryer area which means that it evaporates and barely reaches or could not reach the surface at all, the only thing it does, is create lightning strikes, the well-known dry-lightning. The cooling of the air as a result of the evaporation, makes the air fall more quickly into the surface producing stronger wind conditions at the ground, which, if you also have a fire, complicates the scenario even more. So generally speaking, and in a hypothetical way it’s something you can experience with the dryer conditions. But it still strongly depends on when your air is coming from… if it’s moist air from the Mediterranean you won’t notice this effect, you will have plenty of rain with soil conditions turning back to moist.

The complex thing about weather is that there are always a lot of different factors combining. If you are talking about the heating, yes, that’s climate change but you have to average it over a period of at least 30 years to see that effect, because you have lots of factors contributing: the higher- or low-pressure systems, how warm is your sea, to know if it produces more moisture in the air that comes to the land, etc.

We have been discussing that weather conditions have been changing over the past years, so the next questions is how reliable are the weather models if they were developed under different conditions? Why sometimes seem they fail to make short- and long-term forecasts?

First, I need to say that models are continuously being improved for the same reason you marked and also because technology also evolves and makes that possible. On the other hand, it’s important to have a clear idea in what situations you’ll be using them. I like to make an analogy with popcorn… when you talk about thunderstorm and precipitation at a more local scale, we get a signal from the model that those showers will be there in a certain area and they give us an idea of how strong it can be, if they move fast, slowly, if they produce more or less rain, but for those types of showers you need a higher resolution model that can only calculate well one or two days ahead to get a better idea of it. Models with lower resolution like GFS or ECMWF, can give an indication but they will have difficulties to forecast such weather, it’s very depending on the availability of those models. So, if I expect a thunderstorm, I can get a signal from ECMWF but I can’t give you details, and even some of them might change. In that sense, I relate this to popcorn because when you put popcorn in a pan and produce heat underneath, which is similar to when a storm is coming, when putting the popcorn nobody can point which grain will pop first and that certain grains won’t pop at all. It’s the same with weather. I can give you the signals, the conditions, but in the end, you can’t forecast the exact location and intensity with precision because you are dealing with very small-scale and dynamic processes that are difficult to capture with weather models. However, when talking about models, I don’t think they fail to produce short- and long-term forecast. It’s very depending on what you really expect from them and which model you use to answer your questions. What’s your goal with the model and what they produce and can tell you…

Before concluding, what do you think we would need to reverse the situation, what has to change at an atmospheric level?

It’s clear that to reverse the dryness situation of several years, you need a lot of rain. Preferably not within two weeks, because most of it will get lost and you’ll get a lot of flooding, but a lot of rain over a relatively long period of time. That means you need a certain structure in the atmosphere where the Jetstream, that reinforces the effect where it will rain or will be dry, must be in the right way. When you see Europe and the interaction with the Jetstream, you will always find differences. So, if one place is wet, the other place will be dry. You can have conditions where there are widespread showers and thunderstorm, but the most typical thing is to have these two contrasts.

When we talk about Jetstream we talk about two conditions: where is just one Jetstream that does the job with low pressure above it, and low pressure below, but then is that the Jetstream splits in two branches, when one Jetstream goes south, for example, Spain is above the Jetstream, meaning it gets low pressure areas with rain and storms, and the other branch goes further to the north, like Scandinavia. Central Europe, Including the Netherlands, will be stuck between the two branches of the Jet Stream. As a result, it is stuck in a weather pattern with high pressure. It shows that in order to get certain (un)favourable weather, you need the Jet streams in a favourable formation. In the end, we cannot affect this, and we can only hope conditions will be moist enough to keep the fire season controlled.

That's right, it will depend on how the weather continues in the following weeks and how the summer will be. Vegetation is already affected and therefore, sooner or later we will have complex fires that will be a challenge to extinguish. Therefore, it is important to anticipate what will happen this year or at the latest in the following years, and we, at TEP, are committed to training and strengthening human resources in terms of intellect and response capacity...

Thank you very much, Brian, for your time and for sharing your knowledge with us on this occasion.